Why do so many Hungarians keep voting for the ruling party, Fidesz? Political analysts have been trying to find the answer to this question for several years. There are multiple explanations, some of them are supplementary, others are contradictory to each other.

Fidesz has won landslide victories in two other consecutive parliamentary elections (2014 and 2018) since then. It has two thirds parliamentary majority, which enables it to change the constitution without the consent of the opposition. It achieved a concentration of power unprecedented in most other contemporary democracies.

Although conspiracy theories about direct election frauds and the rigged voting system are popular among some opposition circles, most experts believe that elections in Hungary are free, just not fair. Yes, the Hungarian electoral system has been gerrymandered to favor the strongest party, that is, Fidesz. But the disproportional system could not block the opposition from winning the elections and explain the landslide victories of Fidesz in and of itself. There is real but unfair competition – the definition of what Steven Levitsky calls “competitive authoritarianism”. The partial success of the opposition in the 2019 municipal elections is a case in point.

The competition is real but not fair – as if two football teams were playing in a disproportionately sloping soccer field. Fidesz’s core support base has proved to be incredibly solid and resilient over the past ten years; while the opposition’s voting base is fragmented and vulnerable.

According to a recent public poll conducted by the IDEA Institute, the Fidesz supporting base has three characteristics:

1) Ideological homogeneity: 91 percent have a right-wing conservative worldview;

2) Good ability to preserve and gain votes: 20 percent of its voters were converted from those who voted for other parties before;

3) Strong political loyalty and commitment: most of its voters have strong sympathies toward the ruling party and strong feelings against the opposition.

How has Fidesz maintained their base, despite all the corruption scandals and abuse of power reported by the press? There are a number of important elements at play here, based on a selection of recent studies.

1. Informational autocracy

One obvious explanation for Fidesz’s seemingly unshakable popularity is the biased and polarised media landscape in Hungary, dominated by the well-financed propaganda machine that effectively creates an echo chamber around Fidesz supporters. Sergei Guriev and Daniel Treisman coined the term of informational autocracy to describe how this new type of authoritarianism works. Unlike the brutal, bloody dictatorships of the 20th century, the new generation of illiberal leaders in the 21st century have managed to concentrate power without cutting their countries off from global markets or resorting to terror and mass imprisonment. They do so mainly by manipulating the flow of information – not by silencing or censoring the press but by creating a loud noise of pro-government propaganda that distract public attention, thematise the public discourse and relativise truth. They only resort to direct repression in special cases. According to Guriev and Treisman, this formula can be successful among the masses of less educated, less informed citizens, who can be easily manipulated.

How strong is the media bubble?

I wrote this article from the house of my father-in-law, who lives in a village in North-East Hungary. A 72-year-old retired factory worker, he has always leaned left as a voter. He lives in an area that used to be a Socialist stronghold up until the 2000s. This changed after 2010, when Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party won a landslide victory, converting formerly red counties like Borsod too. And this political shift has proved to be stable.

The main source of news and information for my father-in-law has always been the regional newspaper, Észak-Magyarország (Northern Hungary), which calls itself an “independent daily”. A few years ago it was purchased by Mr. Lőrinc Mészáros and it now provides biased, pro-government coverage. Still, it remains the only printed newspaper he reads because it has local news. Many people like him have become the involuntary consumers of government propaganda as they would like to stay informed about what’s happening around them. When elderly, less educated people are constantly bombarded with news about the migrant threat, the competent and strong government vs. the incompetent and stupid opposition, they will not be unaffected.

The Hungarian media landscape is extremely polarised and the information flow is strictly controlled – especially with regard to those living in disadvantaged communities in the countryside. Government support is stronger among the uneducated and those without internet and media access. The government now has full control over local newspapers, radios, and television channels in smaller towns and in villages.

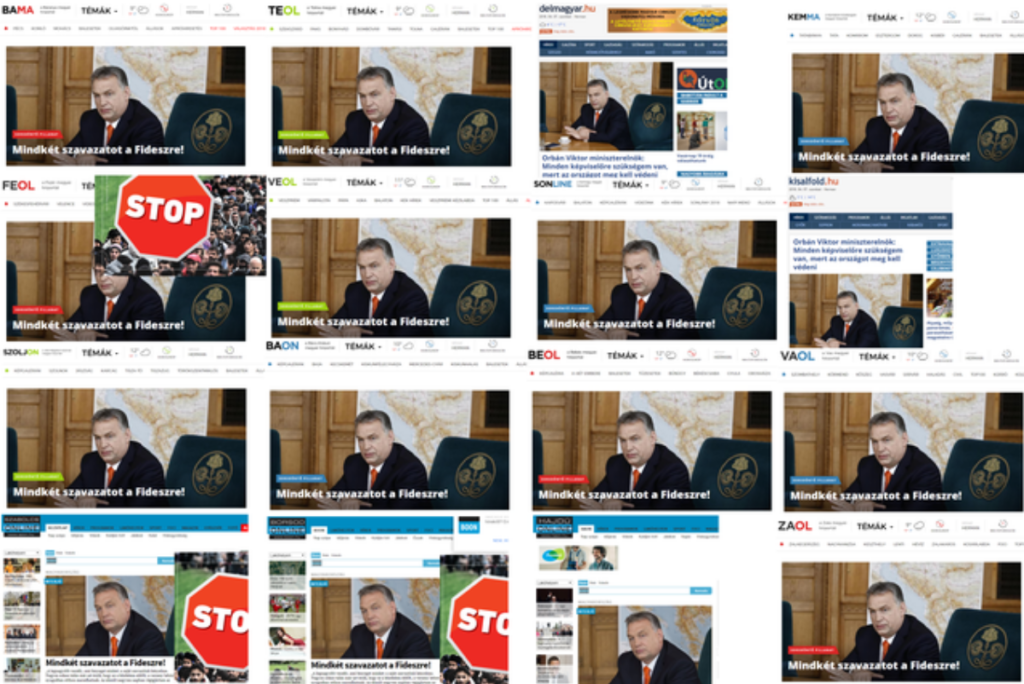

The picture below illustrates the poor state of press freedom in Hungary well: it shows the front pages of local newspapers in Hungary before the 2018 parliamentary elections. Same headlines, same message (“both votes on Fidesz”) – same picture of Mr. Orban. All these local newspapers are owned by Mr. Lőrinc Mészáros, the personal friend of Mr. Orban, a simple gas pipe fitter who has become a billionaire and who happens to live in the home village of the prime minister. In the countryside, where the main source of news for many people (especially the elderly) are local newspapers, this effectively creates a reality bubble which is very hard to break for the opposition.

As a study points out, however, that the bubble does not isolate people perfectly: even ardent pro-government voters have some access to independent media. The problem is that independent news sources that try to provide a balanced view and proportional coverage are no match for the indoctrinating effects of the one-sided, manipulative government propaganda that constantly flows from pro-government news outlets.

2. Conflict generation – enemy building

The leaders of the Hungarian version of informational autocracy have gained proficiency in creating public enemies, generating artificial conflicts with these enemies and exploiting these conflicts by indoctrinating and mobilising their voters. The most infamous example is of course George Soros, the Hungarian born American billionaire, who, ironically, gave a grant to Fidesz that enabled it to run in the first parliamentary elections in 1990.

It is well documented how Fidesz secretly invited Arthur Finkelstein, the American political advisor, to help them to design a successful, negative campaign in 2008. It was Finkelstein who recommended that Orban make Soros public enemy number one. Building on the post-financial-crisis anxieties among voters, he suggested constructing an external enemy figure who can be blamed for every misfortune – a Jewish banker who is plotting against Hungary.

The secret formula worked better than Finkelstein could ever dream of. In the past ten years, Fidesz has spent tens of millions of dollars on billboard posters and televised ads to implant the idea into the minds of people that Soros leads a world conspiracy against Hungary, with the goal of settling millions of Muslim migrants to Europe and destroying its Christian roots.

3. “National consultations”: the myth of a direct democracy

The Soros Plan Conspiracy remains the core of Hungarian government propaganda, which tries to establish itself as the voice of “The System of National Co-operation” – a regime that has a strictly voter-first approach. “National consultations” are printed questionnaires sent to each and every voting citizen to serve this goal. They often include leading questions about just how dangerous George Soros is for Hungary .

Fidesz has organised eight national consultations since 2010. The last one was launched a few weeks ago, with a question suggesting that Soros wants to force Hungary into debt servitude by promoting the introduction of COVID-bonds in the EU. “National consultations” offer the (fake) opportunity to “the people” to have a say in the governance of the country, creating the illusion of a direct dialogue between people and government. Constitutional checks and balances, independent institutions and judiciary, free press and critical NGOs – they are all portrayed as trying to obstruct this direct and intimate relationship between the Hungarian people and its government. They are shown as serving foreign elite interests -as a threat to “real democracy”.

4. Poll-driven governance

Apart from “national consultations”, the government also heavily invested in other centralised propaganda campaigns. For this purpose, the prime minister created a communications cabinet, and put Antal Rogán in charge of it. Rogán is responsible for “government communications”, and coordinates this element of the well-financed propaganda machine. Dubbed the Propaganda Ministry by the independent press, the department’s annual budget is estimated to be 133 billion HUF(420 million USD) this year.

The Propaganda Ministry contracts analytics and advisory companies to carry out at least two public polls a week, to monitor the slightest changes in the mood and opinions of the Hungarian public. Sources close to the government claim that these polls have a very important role in identifying the next targets of government policies. They test ideas about who should be labeled public enemy next. Evidence-based policy making or consultation with professional organisations plays no role in preparing new laws and policies in Hungary – new policies are measured on the grounds of how useful they are to concentrate power and maintain public support.

5. It’s the economy, stupid!

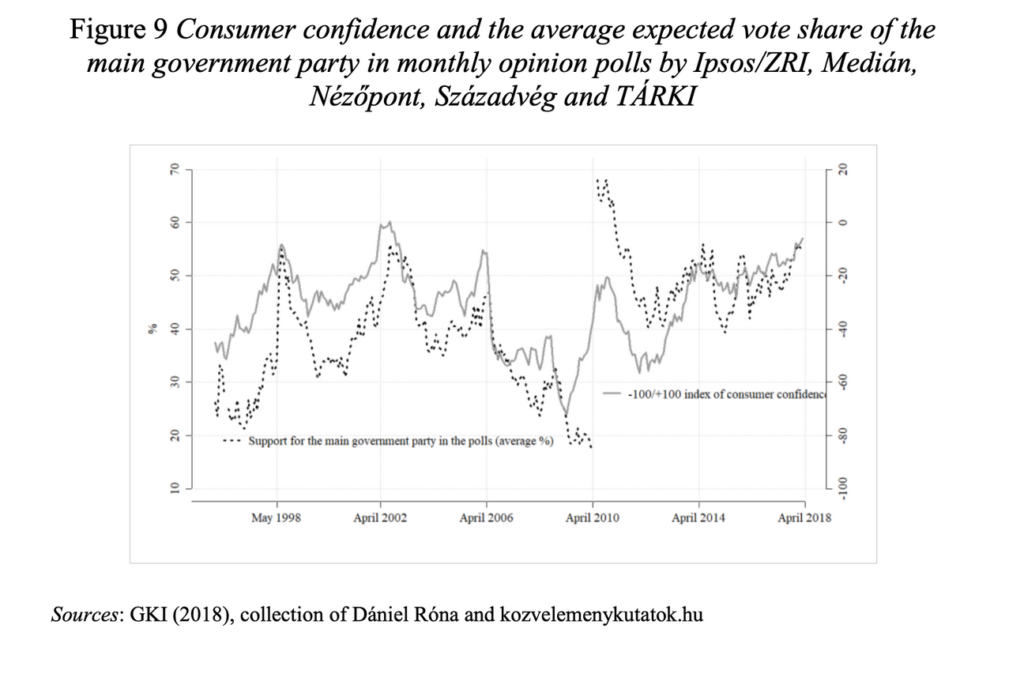

Gábor Tóka, a political analyst at Central European University, infers that economic factors play an important role in shaping the judgement of people to support Fidesz. He points out that there is a stable and consistent correlation between the popularity of the government and the trends recorded by the consumer satisfaction index, an economic indicator that measures the satisfaction of consumers (see the graph below). How people see their economic prospects is a significant indicator of their voting preferences. According to Tóka, even more so than all the negative campaigns inciting hatred against migrants and Soros.

There is no doubt that the relatively stable economy that enabled the middle class to save plays an important role in keeping Orban in power. Orban may like to be seen as a rebel and culture warrior who protects Hungarian interests against the West but his system is built on a symbiotic relationship with German capital. As The Economist pointed out recently, the Hungarian economy is export-dependent (85 percent of its GDP comes from the export of goods and services) and is closely tied to the German economy. Merkel spectacularly dislikes Orban, but she is aware of the importance of cheap Hungarian labour in operating German car factories, so she avoids direct confrontations and tolerates the industrial-scale corruption and crony capitalism in Hungary.

6. The poorer you are – the more likely you are to vote for Fidesz

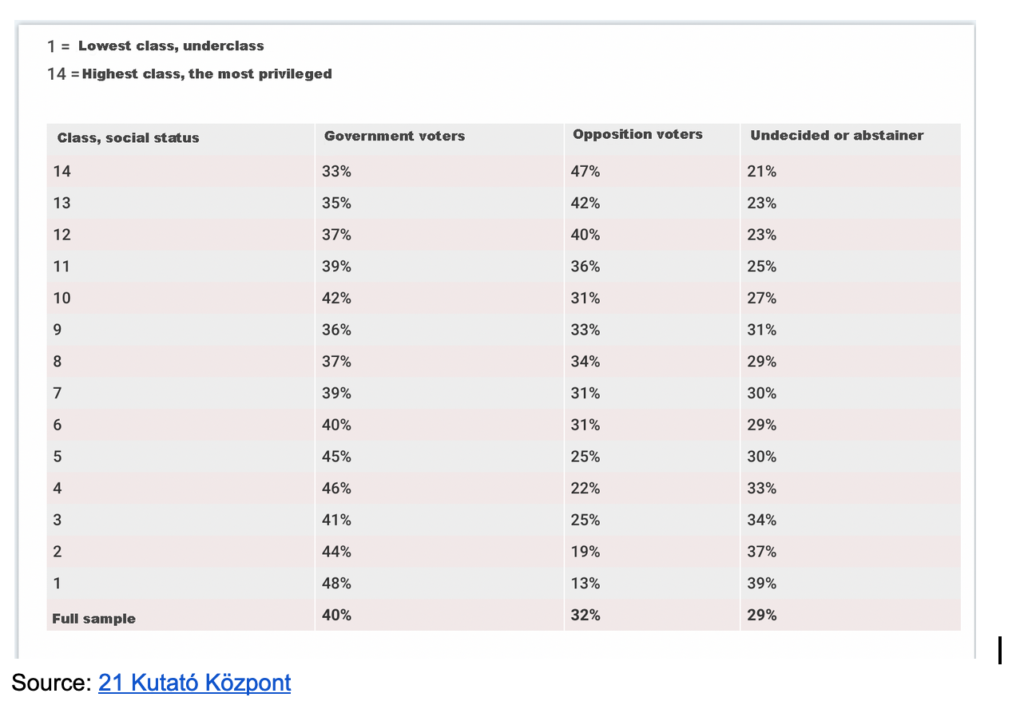

If people adjust their voting preference to their economic prospects, you may expect that people who are doing better will vote more to the government. But according to a recent study conducted by Research Center 21, a new think tank, this is not the case. The top decile of Hungarian society predominantly votes for the opposition. As you move down the social ladder, the popularity of Fidesz grows exponentially.

Remarkably, Fidesz is most popular among the most vulnerable who did not profit much from economic prosperity. Meanwhile the most privileged, who benefit most from the regime, would rather oust Fidesz.

The divide between wealthy and poor is highest in rural areas and the slightest in Budapest. Deprived, disadvantaged, uneducated people living in small towns and villages are likeliest to vote for Fidesz. The opposition could not even attract more voters among those 30 percent of respondents who see their economic situation as worsening – and the more disadvantaged they are, the less likely they are to turn against the government.

System justification

Researchers used the System Justification Theory (SJT), constructed by social psychologist John T. Tost and his colleagues, to explain the findings. This theory holds that individual needs can often be satisfied by defending and justifying the status quo, even if the system may be disadvantageous to the same people. For some people it is easier to accept the injustices and inequalities of the hierarchical system as the reflections of a just moral order than to deal with the psychological stress that accompanies constant system criticism. Oppressive regimes offer alternatives to rationalise injustices by creating enemies to hate – such as marginalised groups like migrants, the homeless, or other minorities. Although we could expect more solidarity from those belonging to the underclass towards other disadvantaged groups in society, often the opposite is true: they tend to reject them even more.

When you allow people to choose between the corrupt and the stupid, they will go for the corrupt.

as Arthur Finkelstein, the mastermind behind many sinister election campaigns put it.The government’s anti-migrant propaganda is much more successful among these people than the opposition’s anti-corruption campaigns because crimes committed by the wealthy and powerful ruling elite are justified by the moral world order they believe in. Government propaganda pushes the image of strong and competent leaders who protect the “man on the street” from internal and external threats.

7. Public works program: a political tool

The public works program is another important factor in sustaining support among the most disadvantaged groups in rural areas. The official justification of this program was to reintegrate unemployed people into the labour market by providing them the opportunity to have a paid job in public work projects.

But according to critics, including the EU Commission, the program does not lead people back to the workforce. It preserves their disadvantage and keeps them in a semi-feudal dependence on local oligarchs. Research Center 21 found that Fidesz was significantly more successful in growing its base in localities where a public works program operates. What is more, the public works schemes had this effect mostly in those places where the mayor belonged to the ruling party. This seems to support the claims that the public works scheme is used for political clientelism and social control.

Prospects in the post-COVID era

Those who predict that Orban’s system will be overthrown by the poor and disadvantaged classes, who lose out the most as a result of the industrial theft of public resources and the downtrodden educational, social, and health care systems, are not vindicated by the research findings described above.

It seems Fidesz could effectively cement its power in Hungary by mobilising the votes of the poor and uneducated masses, partly by dominating the flow of information and partly by controlling disadvantaged communities with tools like the public works scheme. People tend to tolerate corruption and rights violations as long as they feel that their existential security is protected by leaders who are perceived to be competent. But what happens when this perception of existential security and competent leadership is gone?

The COVID-19 epidemic is a major threat to the Orban regime’s stability, but so far it has not caused serious disturbances. The toll of the epidemic in Hungary is perceived to be relatively mild and poll findings show that people believe that the government’s countermeasures were effective. A public poll conducted by Publicus found that one quarter of the population experienced a significant existential crisis during the lockdown. Among them, 4 percent lost their income completely.

Most Hungarians did not attribute the hardships to an inadequate government response. According to the findings of another public poll, Fidesz might strengthen its base during the COVID-19 pandemic, although it would lose the election if only people under 30 years old could vote.

As a second wave of the pandemic is closing in on neighboring countries, Fidesz’s popularity may be put to the test. What will happen if a serious second wave hits the country and/or the economy cannot regenerate as fast as the government promised? Can this change the political landscape before the 2022 parliamentary elections? Will Orban resort to harsher repressive measures if his popular support wanes?

Contributed by Peter Sarosi

Illustration by Istvan Gabor Takacs.

Péter Sárosi

Executive Director of the Rights Reporter Foundation.

He is a historian, a human rights activist and drug policy expert, the founder and editor of the Drugreporter website since 2004, a documentary film maker and blogger. He has been working for the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU) for more than 10 years. Now he leads the Rights Reporter Foundation.